Here is a brief excerpt from an article written by Sven Smit for the McKinsey Quarterly, published by McKinsey & Company. To read the complete article, check out other resources, learn more about the firm, obtain subscription information, and register to receive email alerts, please click here.

To learn more about the McKinsey Quarterly, please click here.

* * *

Strategy plays out in a world of probabilities, not certainties. That’s why you need to know your odds

My colleague and co-author Chris Bradley recently wrote about the perils of the social side of strategy —how “egos and competing agendas, biases and social games” affect the decisions made in the strategy room. There is another dangerous pitfall that I often see trip up management teams striving to develop corporate strategies: the tendency to seek certainty when you should be gauging odds.

Consider the difference between poker and golf. In general, the more skill is involved in a game, the less you need to think about probabilities. If I played a world-class golfer -someone like Bernhard Langer or Rory McIlroy -I’d never win a game against him. On the other hand, the more that luck (or uncertainty) is involved, as in poker, the more you need to ponder the odds. In poker, I’d not only have a chance to win a hand against a world-class player like Phil Hellmuth but would even occasionally beat him, as people do. Hellmuth would certainly beat me over time, but, in the short run, I’d have a chance.

In business, as in poker, there is uncertainty, and strategy is about how to deal with it. Accordingly, your goal is to give yourself the best possible odds. People shouldn’t just get credit for winning and demerits for losing. If five companies each have an 80% chance of succeeding, that still means that one will usually fail. If five companies each have a 20% chance of success, one of the five is still likely to win. Clearly, the superior strategy is the one with an 80% chance of success.

In business, as in poker, there is uncertainty, and strategy is about how to deal with it

Risk, of course, needs to be part of the probability discussion, too. If you have just a slim chance of winning, but a bet costs you little and the potential win is huge, that still may be an investment worth making. The converse is true, too: An expensive investment that generates a high probability of a small success may be a bad idea. Poker players refer to their calculations as “pot odds.” If a $100 bet gives you a 20% chance of winning a $200 pot, you fold. Essentially, you’re paying $100 for $40—that 20% of the $200. But a $100 bet that gives you a 20% chance of winning a $2,000 pot is one you make every time, because you’re paying $100 to get $400—20% of $2,000. Likewise, in business, an assessment of your odds—in terms of competitive, market or regulatory factors—needs to be part of your calculation.

What are your odds?

In a recent post, Martin Hirt, another McKinsey colleague and co-author, described the Power Curve of economic profit – the result of a four-year study we recently conducted that is the subject of our upcoming book, Strategy Beyond the Hockey Stick.

Chris Bradley explains the characteristics of the Power Curve here:

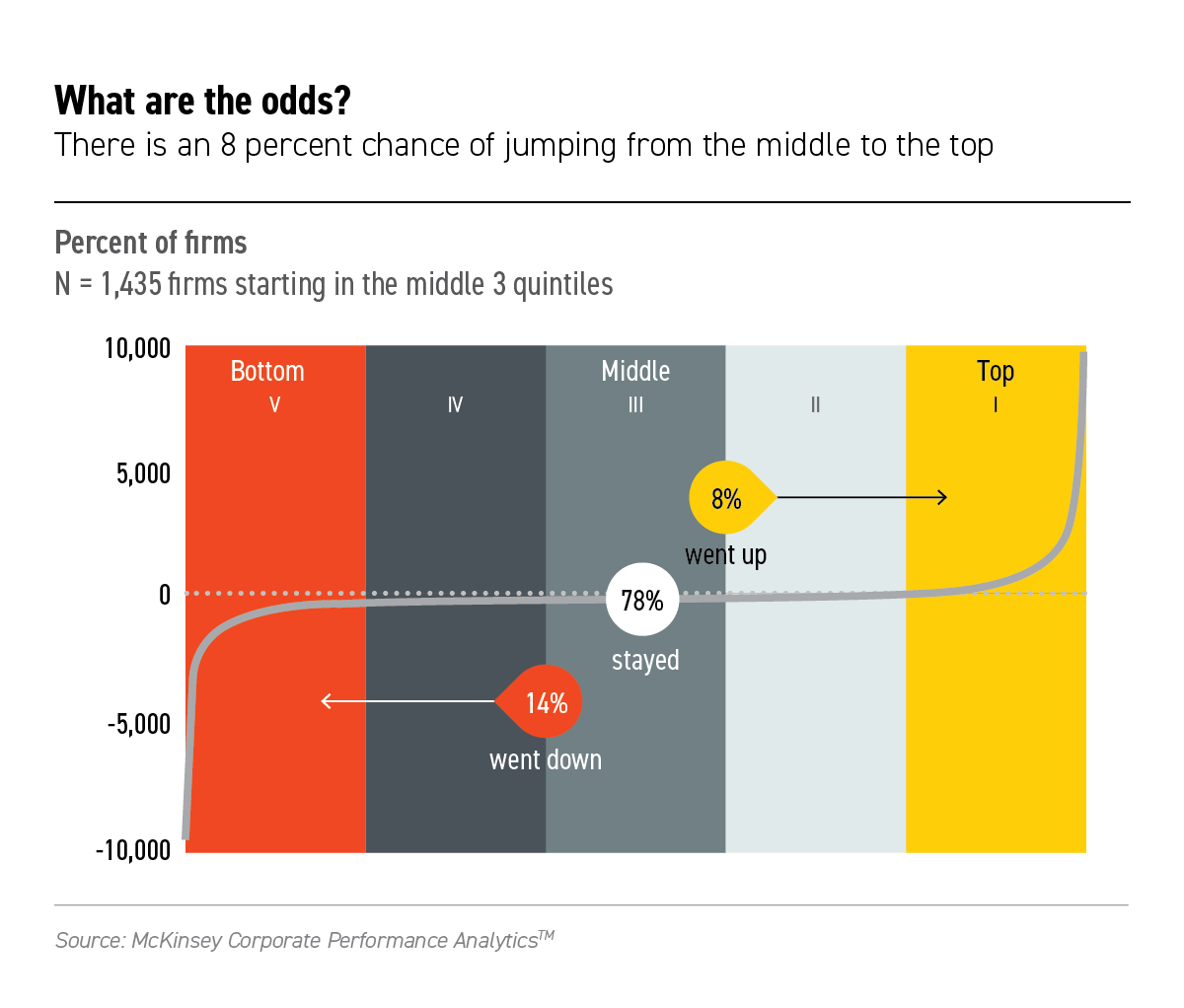

The Power Curve shows a broad swath of companies with middling performance bracketed by steep tails. But what are the odds of moving up or down the curve? At the highest level, your odds of making a move across the quintiles over a 10-year period, if you started in the middle three quintiles, are shown in the chart below.

As you can see, your odds of going from the middle quintiles to the top quintile are 8%.

Eight percent!

Let that sink in for a moment. Of all those strategies that boldly projected growth and got approved a decade ago, not even 1 in 10 made it. And the entire curve is rather sticky. Almost 80% of firms in the flat middle stayed there over the decade we studied.

The odds of individual business units moving up and down the performance curve are roughly the same as for companies. And, when companies make a big move up the curve, it is mostly because one, or at most two, of their businesses made a hockey stick-style surge. Think about that for a moment. If you have a portfolio of 10 businesses, chances are that only one will break out over a 10-year period—and correctly identifying that one and feeding it all the resources it needs will most likely determine whether your company as a whole can make a significant move up the Power Curve.

* * *

Here is a direct link to the complete article.

Sven Smit is a senior partner in McKinsey and Company’s Amsterdam office and leader of its Western European region. He is also the author, with Martin Hirt and Chris Bradley, of Strategy Beyond the Hockey Stick: People, Probabilities and Big Moves to Beat the Odds, published on February 13, 2018.