Here is a brief excerpt from an article written by Rahil Jogani, Sanjay Kaniyar, Vishal Koul, and Christina Yum for the McKinsey Quarterly, published by McKinsey & Company. To read the complete article, check out other resources, learn more about the firm, obtain subscription information, and register to receive email alerts, please click here.

To learn more about the McKinsey Quarterly, please click here.

* * *

Automation has great potential to create value—but only for businesses that carefully design and execute it.

Encouraged by the much-vaunted potential of automation, organizations around the world are embarking on their own transformation journeys. On paper, the numbers look compelling. The McKinsey Global Institute estimates that about half the activities that workers are paid $15 trillion in wages to perform in the global economy have the potential to be automated by taking advantage of current technologies (see sidebar, “Key automation technologies”).1 Looked at another way, at least 30 percent of work activities in about 60 percent of all occupations could, in principle, be automated.

With their eyes on the automation prize, companies have set aspirational targets that run to hundreds of millions of dollars. As they launch their first, second, and third waves of automation, however, most are finding it harder than they expected to capture the promised impact. In our experience, about half of current programs are delivering value on some fronts, but only a handful are generating the impact at scale that their business cases promised.

Teething troubles are to be expected with an effort as wide-ranging as automation. Applying a largely unfamiliar portfolio of technologies in a fast-moving, complex business is enough to break even the most experienced leaders and teams. In the C-suite, executives are approving major investments that promise generous paybacks in a matter of months; meanwhile, down on the factory floor, project teams are constantly scrambling to extend timelines and trim back impact estimates. We have seen RPA programs put on hold and CIOs flatly refusing to install new bots—even when vendors have been working on them for months—until solutions have been defined to scale up programs effectively.2 In case after case, early adopters are left writing off big investments.

Though the reasons for poor results vary, we see three common execution pitfalls that derail automation programs.

Underestimating the complexity

At one global bank, leaders developed a multimillion-dollar business case for automation. First up in the program was basic RPA. Estimates of the potential value that could be captured in the first year shrank from 80 percent to 50 percent to 30 percent, and finally less than 10 percent once development got under way. The effort quickly lost traction. A platform combining RPA and AI was then proposed and developed for more than a year, but much the same thing happened again.

Treating automation as a technology-led effort can doom a program to failure. Process problems can rarely, if ever, be tackled simply by introducing a new technical solution. Often there are many underlying issues—poor quality of input data, accommodating too many client variations, “off script” procedures that cannot be quickly understood in high-level process demonstrations or requirements documents. The reality is that automation solutions are complex because they tend to affect multiple processes with significant interdependencies across technologies, departments, and strategies. If these issues and elements are neglected, they tend to undermine a company’s automation objectives during implementation. Other more thoughtful approaches—process reengineering, organization redesign, policy reform, technology-infrastructure upgrades or replacements—need to be considered in parallel with automation solutions.

To ensure that automation complements rather than clashes with other strategic priorities, senior leaders, technology experts, application owners, and automation teams need to work together to define a joint vision for how business processes will function in the future.

Companies that succeed with automation take care to base their vision on reality. They start by understanding their technological maturity, tracking customer and employee touchpoints, mapping information flows, and setting expectations for exception handling, metrics, and reporting.

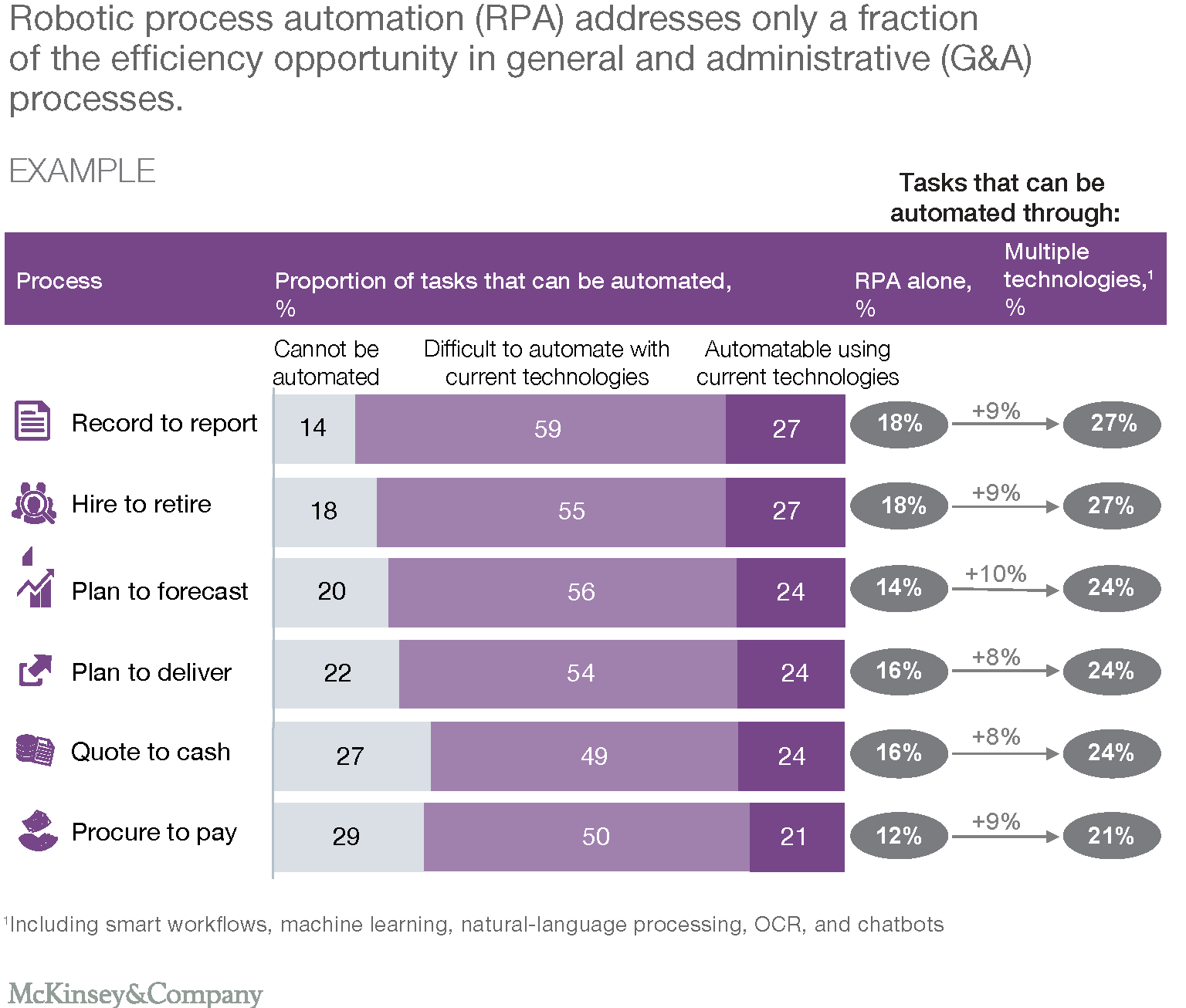

This is generally known as enterprise architecture management. Taking an end-to-end view of processes enables companies to shape and prioritize automation initiatives. This clear view also allows the business to better pinpoint which of the various automation technologies are most appropriate and how they can be combined to create more value. For instance, an organization by introducing a basic RPA program could address 12–18 percent of general and administrative tasks by itself, but the addition of smart workflows, NLP, cognitive agents, and other technologies helped increase the scope for automation to 21–27 percent (Exhibit 1). Combinations of technologies can also deliver other benefits, such as shorter cycle times and better quality.

When one enterprise decided to overhaul its customer-care operations, for example, it began by scrutinizing the journeys customers took to complete a given task. After creating a comprehensive view of the various processes and dependencies, it was able to set targets and select solutions with clear business outcomes in view. These included automating basic front-line processing using chat and voice-enabled cognitive agents; offering online self-service for 30 to 60 percent of customer transactions; seamlessly integrating customer journeys with back-end transactions and servicing; improving response times; integrating social, messaging, digital, and voice-driven channels to develop omnichannel customer inputs; and having a clear view of strategic customer-relationship management (CRM) tools, systems, and interfaces to lay the foundation for automation.

Armed with this process-centered vision, automation teams had a clear framework within which to plan and execute their initiatives. Because they had a clear grasp of their scope, accountabilities, and expected impact on the business from the outset, they were able to minimize duplication of effort, tackle dependencies between systems and processes more easily, and better manage change both for the customers using the new features, services, and channels and for the teams introducing and supporting them.

* * *

Here is a direct link to the complete article.

Rahil Jogani is a partner in McKinsey’s Chicago office, Sanjay Kaniyar is a partner in the Boston office, Vishal Koul is a specialist in our Stamford office, and Christina Yum is an expert in the New York office.