Here is a brief excerpt from an article written by Michael Birshan, Carolyn Dewar, Thomas Meakin, and Kurt Strovink for the McKinsey Quarterly, published by McKinsey & Company. To read the complete article, check out other resources, learn more about the firm, obtain subscription information, and register to receive email alerts, please click here.

Here is a brief excerpt from an article written by Michael Birshan, Carolyn Dewar, Thomas Meakin, and Kurt Strovink for the McKinsey Quarterly, published by McKinsey & Company. To read the complete article, check out other resources, learn more about the firm, obtain subscription information, and register to receive email alerts, please click here.To learn more about the McKinsey Quarterly, please click here.

* * *

Many new CEOs reshuffle their top teams, but surprisingly few make them more diverse. Can we do better?

Diversity matters in the workplace. It is an important social issue, and a performance imperative: more diverse top-management teams appear to benefit from a richer decision-making dialogue, which can contribute to better financial performance.1

A missed opportunity

At the beginning of their tenures, new CEOs typically change the makeup of their management teams. Our research shows that more than two-thirds of chief executives replace at least half of the members of their top teams within two years of taking office.2 They may do so to strengthen the capabilities of those teams, to embark on new strategic directions, or simply to replace former peers they had competed against for the top job, who may have different ideas about the way ahead. The management reshuffles that happen during transitions hold the potential to serve as “unfreezing moments,” dramatically improving the representation of women at senior levels and sending a strong signal to the organization that this issue matters and that the CEO expects to increase gender diversity going forward.

Yet only a small number of new CEOs are taking advantage of the narrow window of opportunity a transition provides to boost the top team’s diversity (see sidebar, “About the research”). For example, we found that within three years, gender diversity in senior teams that new CEOs reshuffled increased by only two percentage points—raising the proportion of women in management to only 14 percent, from 12 percent. The picture of female representation didn’t improve when we expanded the time period to cover management reshuffles over the entirety of the CEOs’ tenures.

This finding suggests that even if a dearth of women in the management pipeline limited progress during the transition period, those same CEOs didn’t change the pipeline and promotion picture during their tenures. The trend was consistent across time as well: CEOs who took charge in recent years were no more likely to promote women to senior roles than those who became corporate leaders 20 or 30 years ago. And though our data focused solely on gender, research by our colleagues on the additional difficulties faced by women of color suggests that top-team transitions do little to help on that front either.3 Behind all the apparent inaction—and missed opportunities—we found three complex underlying patterns.

Up from the bottom

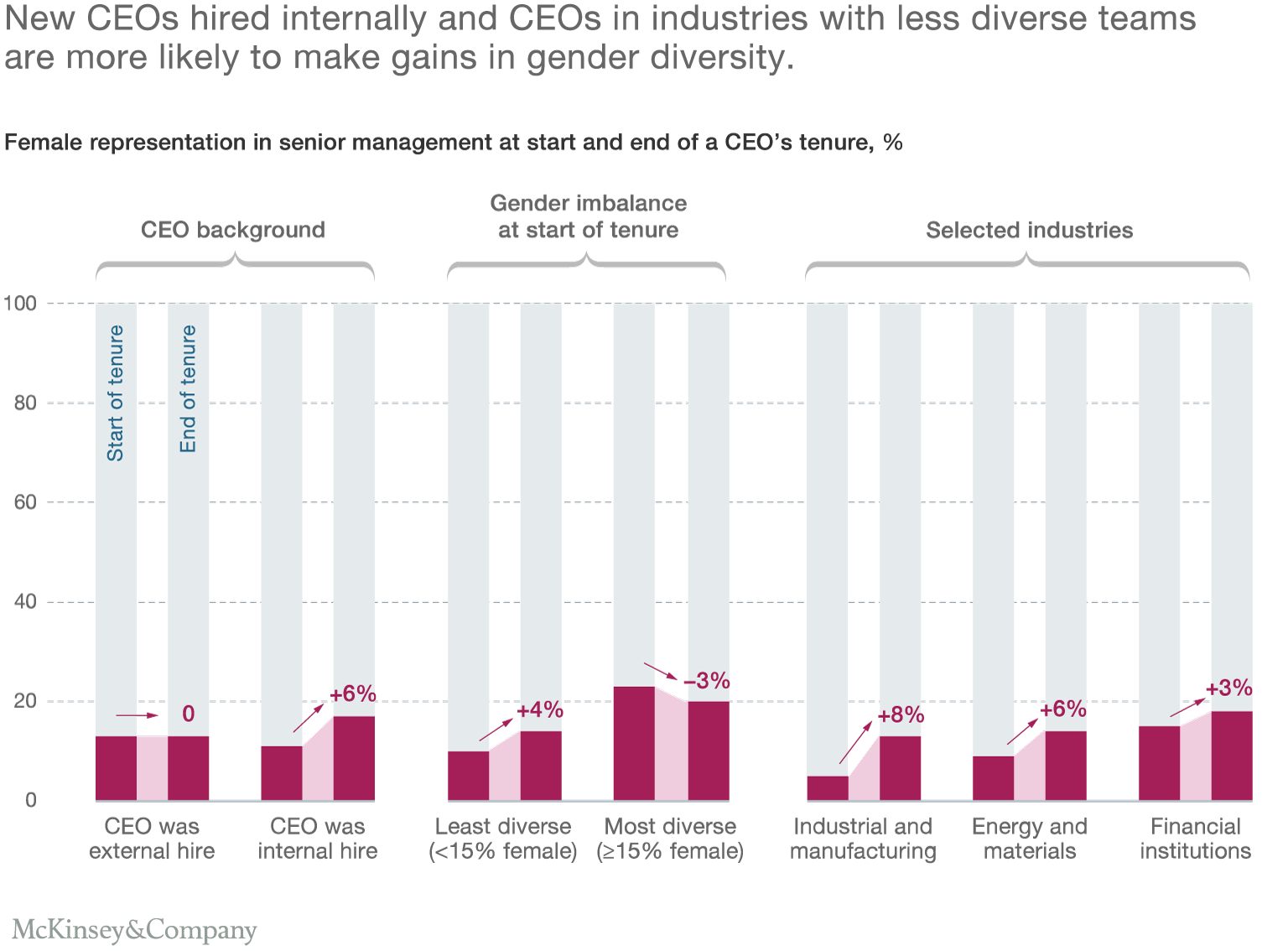

First, new CEOs in the least diverse companies and industries seem to make the most significant improvements in gender diversity over the course of their tenures (exhibit). Chief executives who took over companies where women made up less than 15 percent of the senior-management team, for example, increased female representation, on average, to 14 percent, from 10 percent—twice the level of improvement achieved by all CEOs who undertook management reshuffles. While the sample size is unfortunately small, the same effects are seen when looking at female incoming CEOs specifically.

Digging deeper, we found that CEOs who take the helm of companies in historically male-dominated industries made the most significant improvements, although the sample size was small. For instance, new CEOs in heavy-industry sectors, which had the lowest levels of female representation at the start of their tenures, more than doubled it on their executive teams, to 13 percent, from an average of 5 percent. Although the companies these CEOs led started from a lower base and had the greatest room to improve, it is still positive that their companies are addressing major imbalances even when the talent pipeline doesn’t make this easy.

* * *

Here is a direct link to the complete article.

Michael Birshan is a senior partner in McKinsey’s London office, where Thomas Meakin is a partner; Carolyn Dewar and Kurt Strovink are senior partners in the San Francisco and New York offices, respectively.

The authors wish to thank Denis O’Connor and Markian Mysko von Schultze for their contributions to this article, as well as Lareina Yee and Vivian Hunt for their expertise as leaders of McKinsey’s overall research on diversity.