Here is a brief excerpt from an article written by Susan Lund, Asheet Mehta, James Manyika, and Diana Goldshtein for the McKinsey Quarterly, published by McKinsey & Company. To read the complete article, check out other resources, learn more about the firm, obtain subscription information, and register to receive email alerts, please click here.

To learn more about the McKinsey Quarterly, please click here.

* * *

The world economy has recently returned to robust growth. But some familiar risks are creeping back, and new ones have emerged.

It all started with debt.

In the early 2000s, US real estate seemed irresistible, and a heady run-up in prices led consumers, banks, and investors alike to load up on debt. Exotic financial instruments designed to diffuse the risks instead magnified and obscured them as they attracted investors from around the globe. Cracks appeared in 2007 when US home prices began to decline, eventually causing the collapse of two large hedge funds loaded up with subprime mortgage securities. Yet as the summer of 2008 waned, few imagined that Lehman Brothers was about to go under—let alone that it would set off a global liquidity crisis. The damage ultimately set off the first global recession since World War II and planted the seeds of a sovereign debt crisis in the eurozone. Millions of households lost their jobs, their homes, and their savings.

The road to recovery has been a long one since those white-knuckle days of September 2008. Historically, it has taken an average of eight years to recover from debt crises, a pattern that held true in this case. The world economy has recently returned to robust growth, although the past decade of anemic and uneven growth speaks to the magnitude of the fallout.

Central banks, regulators, and policy makers were forced to take extraordinary measures after the 2008 crisis. As a result, banks are more highly capitalized today, and less money is sloshing around the global financial system. But some familiar risks are creeping back, and new ones have emerged. In this article, we build on a decade of research on financial markets to look at how the landscape has changed.

- Global debt continues to grow, fueled by new borrowers

- Households have reduced debt, but many are far from financially well

- Banks are safer but less profitable

- The global financial system is less interconnected—and less vulnerable to contagion

- New risks bear watching

Global debt continues to grow, fueled by new borrowers

As the Great Recession receded, many expected to see a wave of deleveraging. But it never came. Confounding expectations, the combined global debt of governments, nonfinancial corporations, and households has grown by $72 trillion since the end of 2007. The increase is smaller but still pronounced when measured relative to GDP.

Underneath that headline number are important differences in who has borrowed and the sources and types of debt outstanding. Governments in advanced economies have borrowed heavily, as have nonfinancial companies around the world. China alone accounts for more than one-third of global debt growth since the crisis. Its total debt has increased by more than five times over the past decade to reach $29.6 trillion by mid-2017. Its debt has gone from 145 percent of GDP in 2007, in line with other developing countries, to 256 percent in 2017. This puts China’s debt on par with that of advanced economies.

Growing government debt

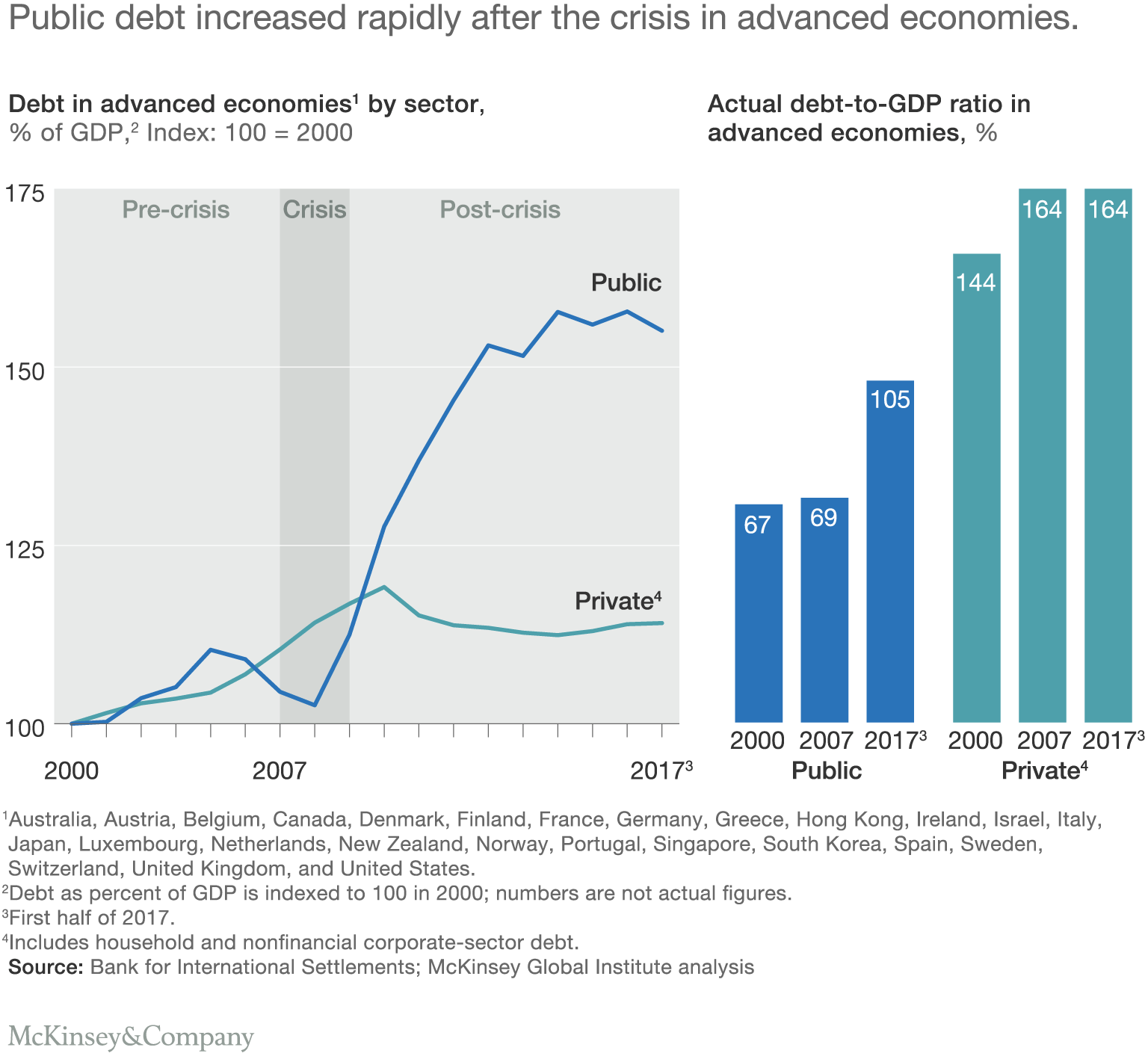

Public debt was mounting in many advanced economies even before 2008, and it swelled even further as the Great Recession caused a drop in tax revenues and a rise in social-welfare payments. Some countries, including China and the United States, enacted fiscal-stimulus packages, and some recapitalized their banks and critical industries. Consistent with history, a debt crisis that began in the private sector shifted to governments in the aftermath (Exhibit 1). From 2008 to mid-2017, global government debt more than doubled, reaching $60 trillion.

Among Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development countries, government debt now exceeds annual GDP in Japan, Greece, Italy, Portugal, Belgium, France, Spain, and the United Kingdom. Rumblings of potential sovereign defaults and anti-EU political movements have periodically strained the eurozone. High levels of government debt set the stage for pitched battles over spending priorities well into the future.

In emerging economies, growing sovereign debt reflects the sheer scale of the investment needed to industrialize and urbanize, although some countries are also funding large public administrations and inefficient state-owned enterprises. Even so, public debt across all emerging economies is more modest, at 46 percent of GDP on average compared with 105 percent in advanced economies. Yet there are pockets of concern. Countries including Argentina, Ghana, Indonesia, Pakistan, Ukraine, and Turkey have recently come under pressure as the combination of large debts in foreign currencies and weakening local currencies becomes harder to sustain. The International Monetary Fund assesses that about 40 percent of low-income countries in sub-Saharan Africa are already in debt distress or at high risk of slipping into it. Sri Lanka recently ceded control of the port of Hambantota to China Harbour Engineering, a large state-owned enterprise, after falling into arrears on the loan used to build the port.

* * *

Here is a direct link to the complete article.